Procrastination is not just delaying things; it is a profoundly entrenched outcome of managing our energy, emotions, and self-worth. Underneath every postponed step is an inner battle that only fear, self-doubt, and mental fatigue can generate.

More than a simple habit, procrastination is a complex cycle triggered by low energy, low self-esteem, and chemical imbalances in the brain.

Before procrastination surfaces, you experience a series of internal conditions. Low self-esteem fuels doubt and anxiety, while the mind instinctively retreats to the comfort zone—a familiar place designed to avoid discomfort. This process activates a self-sabotaging loop, preventing you from taking meaningful steps forward.

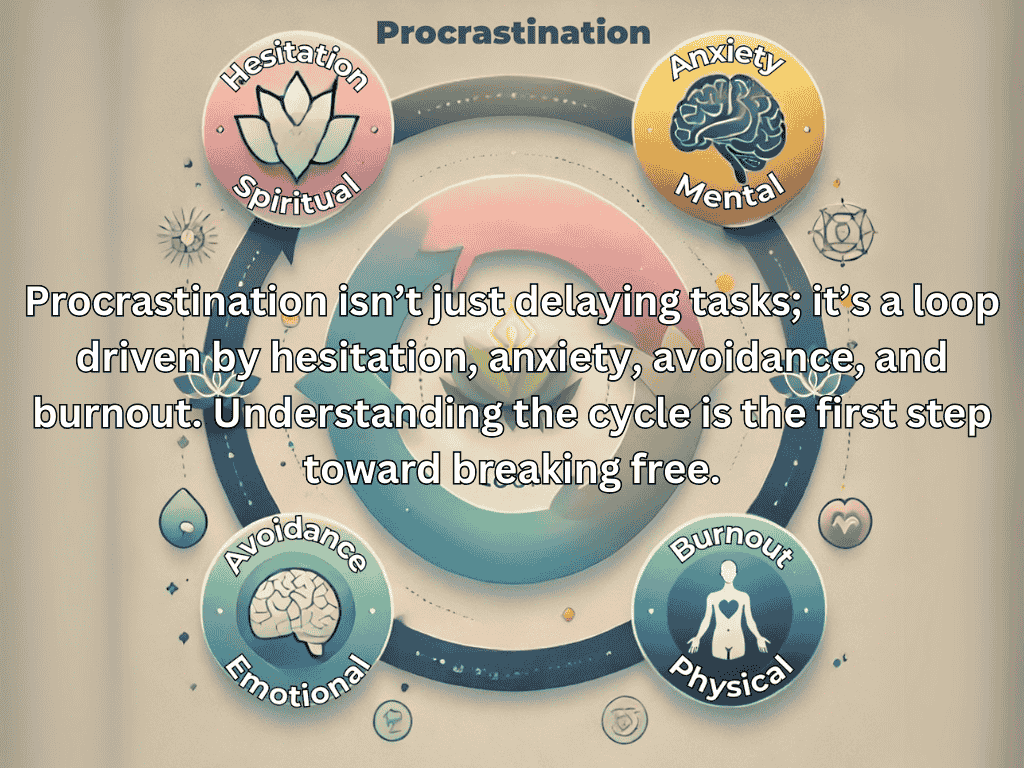

How putting things off turns into a cycle of self-destruction

Procrastination often begins with hesitation, driven by internal doubts. This hesitation triggers anxiety, and as anxiety builds, it creates a mental block to keep itself safe from feeling bad again; the brain often chooses to avoid certain situations. At first, this avoidance provides temporary relief, but over time, it reinforces a pattern of self-sabotage.

Burnout is at the heart of this cycle—a signal that your mind has reached its limits. When burnout sets in, the brain ignores what is healthy and vital and switches its focus to simply existing — get through today and make sure nothing urgent happens tomorrow. Procrastination becomes a coping strategy, perpetuating a vicious loop of not growing and piling on more feelings of failure.

Reflective Question: Can you pinpoint instances where procrastination was self-protection instead of laziness?

Emotional Triggers Behind Procrastination

Emotional triggers are essential factors in the formation of procrastination. Fear of failure is one of the most common triggers—when you fear that you might not meet expectations, avoiding the task seems like a safer option. Perfectionism can just as much paralyze progress because anything less than perfect is somehow unacceptable. Fear of judgment is another trigger in itself. If you do not expect criticism even from yourself, it will do you no good. Over time, these emotions install themselves in memory and develop into a mental environment where procrastination is a healthy means of escaping the person’s uncomfortable feelings.

Reflective Question:

What emotions typically surface when you delay essential tasks? How do they influence your actions?

Decision-Making: The Energy-Driven Process Behind Procrastination

Decision-making isn’t just a cognitive process—it’s one of the most energy-intensive functions in the human body. The brain uses considerable energy, and making decisions requires significant mental effort. When energy depletes, the brain instinctively conserves resources by avoiding tasks that demand effort. This is where procrastination finds its foothold.

Decision-making connects directly to energy creation. Each choice generates powerful momentum, but even simple decisions feel overwhelming when dopamine levels are low or fatigue sets in. The comfort zone personality takes over, convincing you that it’s safer to delay action. Over time, this creates a self-reinforcing loop where even minor tasks become sources of stress and avoidance.

Reflective Question:

How does your energy level affect the choices you make?

The Comfort Zone Personality in Detail

It is a word coined over time that denotes a psychological mechanism that develops to protect you from discomfort. The function protects you from perceived physical, emotional, or mental threats.

While this mechanism can be protective in certain situations, it often becomes a barrier to growth.

This personality activates whenever you try to step out of your comfort zone, triggering thoughts like “What if I fail?” “I’m ready for this.” These thoughts create a sense of unease, leading you to retreat into familiar behaviors—procrastination being one of them. Over time, this reinforces the belief that staying in the comfort zone is safer than facing uncertainty.

Why Dopamine is Key to Understanding Procrastination

Dopamine is essential for proper control of motivation, focus, and reward. It is one of those sub-chemicals that, when leveled out, helps to manage a task and keep the brain motivated to finish the job, or at least close enough. When our levels of dopamine, a chemical in the brain that affects how we think and encourage ourselves, are low, we tend to find tasks less interesting. As a result, we might put things off more often.

This imbalance creates a mental state where quick, low-effort rewards like social media scrolling feel more appealing than completing meaningful tasks. The brain seeks these quick dopamine boosts, reinforcing avoidance behavior. While it may provide short-term comfort, this habit ultimately leads to long-term stress and diminished self-worth.

Low dopamine, emotional triggers, and decision fatigue create the perfect storm for procrastination. The brain identifies the perceived long-term benefit of completing tasks as outweighed by its drive to conserve energy and gain immediate pleasure, leaving you locked in a cycle of avoidance. Reflective Question: When you delay functions that matter to you, what patterns do you notice?

Conclusion: A Reflection on Procrastination

Procrastination is not a bad habit—it’s a defense mechanism born from low self-esteem, low energy, and fear of failure. It’s a deeply ingrained response to internal conditions that push you to prioritize short-term comfort over long-term progress. Understanding procrastination as part of a larger pattern of self-sabotage helps explain why it feels so challenging to break free from its grip.

Procrastination is not a simple act of delay—it’s a complicated experience triggered by how we perceive ourselves, how we intend to spend our energy, and how our brain processes fear and discomfort. In this post, I introduce the more fundamental nuances around procrastination and ask you to consider the context of your patterns and prompts. Ourselves, how we intend to spend energy, and how our brain processes fear and discomfort.